On 3 Aug 2012, on sysfling John Polias wrote:

Any thoughts on whether 'kind of' in the following nominal group is a measure numerative (eg p.334 IFG3) or not. It seems to be less about delimiting than about likening (I suppose likening is also a delimiting strategy).

a kind of giant mutated axolotl

Robin Fawcett replied on the same day:

Dear John (and any others interested in this fascinating area of the lexicoframmar),

I do indeed have 'thoughts' on this matter! Two papers, in fact - but I hasten to add that it's not your fault that you haven't heard of them.

The two papers are:

(1a) Fawcett, Robin P., 2006. ‘Establishing the grammar of “typicity” in English: an exercise in scientific inquiry.’ In Huang, Guowen., Chang, Chenguang & Dai, Fan, (eds.) Functional Linguistics as Appliable Linguistics, Guangzhou: Sun Yat-sen University Press, 159-262. Reprinted from Educational Research on Foreign Languages and Art. No. 2, 3-34 and No. 3, 71-91, Guangzhou: Guangdong Teachers College of Foreign Language and Arts, 2006. 921-52. (Also available as Fawcett 2007c.

(1b) Fawcett, Robin P., 2007a. Establishing the Grammar of ‘Typicity’ in English: an Exercise in Scientific Inquiry.COMMUNAL Working Papers No. 21. Cardiff: Computational Linguistics Unit, Cardiff University (ISSN No. 0967-0254). Reprinted from Fawcett, Robin P., 2006. Available for

fawcett@cardiff.ac.uk.

(2) Fawcett, Robin P., 2007b. ‘Modelling “selection” between referents in the English nominal group: an essay in scientific inquiry in linguistics’. In Butler, Christopher S., Hidalgo Downing, R., & Lavid, J., Functional Perspectives on Grammar and Discourse: In Honour of Angela Downing, Amsterdam: John Benjamins, 165-204.

As you can see from the titles, both papers are about (i) an aspect of lexicogrammar (the phenomenon that I have termed 'typicity' in (1a and 1b) and about the broader concept of 'selection between referents' in (2) and (ii) the methodologies that I used in working on identifying (a) the full range of data that are necessarily involved in considering this topic and (b) the resulting system network, realization rules and summary of the structures generated by the outputs from those realization rules.* Your example is just one of a wide set of data that need to be considered, some with overt realizations, as in your example, and some with covert realizations, as in the ambiguous example The army have recently acquired a new tank [Is it just a single new tank, or a new type of tank?] and BP have developed a new engine oil [which is unambiguous, because the head is a 'mass' noun]. Typicity, overt or covert, occurs quite frequently in most types of text, and I have suggested the concept of a typic determiner to handle its overt realizations. This new element in the nominal group is a later development in the more general concept of 'selection between referents' in the grammar of the nominal group.

Thus, if in five of them the item five is a quantifying determiner, so too are a large number in a large number of them and two kilos in two kilos of sugar - and several other types of determiner. This is on the model of other types of determiner that are filled by a nominal group, as described in Fawcett 2007b. My concept of 'selection' is taken up and used in Mathiessen's Lexical Cartography (1995: 655), where he refers back to my earlier work, which I should perhaps therefore list here too:

Fawcett, Robin P., 1974-6/81. ‘Some proposals for systemic syntax: Parts 1, 2 and 3’. In MALS Journal 1.2, 1-15, 2.1. 43-68, 2.2 36-68. Reprinted 1981 as Some Proposals for Systemic Syntax. Pontypridd: Polytechnic of Wales (now University of Glamorgan).

I would start with Fawcett 2007b, if you have it in your university library (as I expect you do) but there is far more in Fawcett 2006 and 2007a about typicity, and about the use of corpora in resolving the question of what structure to use to model its realizations.

If you, John, or any other interested person, would like an electronic version of either Fawcett 2007a or 2007b (or both), please ask.

Robin

Robin Fawcett

Emeritus Professor of Linguistics

Cardiff University

* It is, of course, the structures that are the outputs from the use of the grammar that are what most SFL grammars in fact describe - rathe than the grammar itself. Grammars such as Halliday's Introduction to Functional Grammar and my Invitation to Systemic Functional Linguistics (Fawcett 2008) are written to provide readers with a descriptive framework for analyzing texts, which is not the same thing as a grammar (which, in SFL, consists of the system network and its associated realization rules/statements).

Blogger Comment:

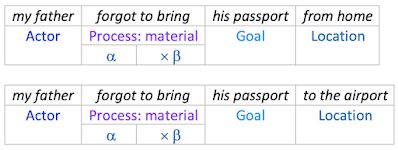

An example of this type of structure is given on p333 of IFG3: a kind of owl, where a kind of is analysed as an extended Numerative, but of the category type (not measure), subcategory variety. These are discussed on the following page.

Using the alias 'Dmytro Poremskyi', Robin Fawcett wrote to sys-func on 23 Sept 2021, at 05:13 and on 25 Sept 2021, at 02:42:

Using the alias 'Dmytro Poremskyi', Robin Fawcett wrote to sys-func on 23 Sept 2021, at 05:13 and on 25 Sept 2021, at 02:42: